The last known thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, died in captivity at Hobart Zoo on September 7, 1936. Its passing marked the extinction of a species that had roamed the Australian continent for millions of years. The few surviving fragments of film and photographs of this enigmatic creature have become haunting relics of a lost world. These grainy black-and-white images are all that remain of the thylacine, a marsupial predator that once held a unique place in Earth’s biodiversity.

In the early 20th century, the thylacine was already a rarity. Decades of hunting, habitat destruction, and government-sanctioned bounties had decimated its population. By the time scientists and conservationists began to sound the alarm, it was too late. The last wild thylacines vanished into the dense forests of Tasmania, leaving behind only myths and whispered sightings. The captive individual that would become the final representative of its species was captured in 1933 and lived just three years in confinement before succumbing to neglect and exposure.

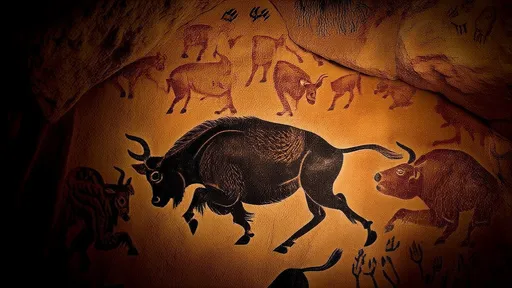

The surviving footage of this animal is eerily silent. In one short clip, the thylacine paces back and forth in its small enclosure, its striped back rippling with each step. It pauses occasionally to stare at the camera with an expression that seems almost accusatory. These images, preserved in stark monochrome, have taken on a symbolic weight far beyond their original purpose. They are not just records of an extinct species—they are a warning.

Scientists have long debated whether the thylacine could have been saved. Some argue that with proper intervention, a breeding program might have been possible. Others believe the species was doomed long before the last individual drew its final breath. What is undeniable is that the thylacine’s extinction was a direct result of human actions. The bounties placed on its head, the relentless encroachment into its habitat, and the indifference to its plight sealed its fate.

Today, the thylacine occupies a strange space in cultural memory. It is both a cautionary tale and a source of fascination. Cryptozoologists cling to the hope that a remnant population might still exist in Tasmania’s wilderness, though no credible evidence has ever surfaced. Meanwhile, advances in genetic engineering have sparked discussions about de-extinction—a controversial effort to bring the species back through cloning. But even if such a feat were possible, it would not undo the lessons of its loss.

The black-and-white archives of the last thylacine serve as a stark reminder of humanity’s power to destroy—and our responsibility to protect. In an age of accelerating biodiversity loss, these images demand reflection. They ask us to consider which species might next exist only in photographs, and what we are willing to do to prevent it.

The thylacine’s story is not unique. Countless other species have vanished due to human activity, often without so much as a photograph to remember them by. But there is something particularly poignant about this creature’s recorded demise. Perhaps it is the clarity of the footage, or the fact that its extinction occurred within living memory. Whatever the reason, the thylacine’s ghost lingers in those flickering frames, a silent witness to our collective failure.

As we move deeper into the Anthropocene, the question remains: will we learn from the thylacine’s fate, or will we continue to repeat the same mistakes? The answer may determine whether future generations inherit a world rich with life, or one where species after species exists only in the grainy archives of history.

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025