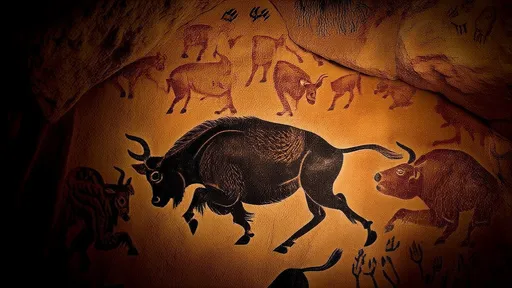

The Altamira bison figures stand frozen in motion upon the cavern's ceiling, their ochre and charcoal forms pulsing with an energy that transcends millennia. These are not mere paintings; they are living testaments to humanity's first attempts to capture the essence of life itself. Discovered in 1879 by a young girl whose astonished cry of "Papa, look! Oxen!" echoed through the cavern, the Altamira cave paintings revolutionized our understanding of Paleolithic art. The ceiling's undulating surface becomes part of the artwork – bulges transform into muscular shoulders, cracks accentuate charging limbs, and the very rock seems to breathe beneath the pigments.

What makes these 36,000-year-old creations so astonishing is their visceral immediacy. The bison aren't static portraits but dynamic creatures caught mid-stride, heads lowered in aggression or bodies coiled to spring. Modern artists would later develop techniques to suggest movement, but these ancient painters understood kinetic energy at a bone-deep level. Their mastery of perspective – showing horns both frontally and in profile simultaneously – creates a dimensionality that flat medieval art wouldn't achieve for thirty thousand years. The famous "fallen bison" with folded legs demonstrates an observational precision that suggests these weren't symbolic stick figures but careful studies of living animals.

The materials themselves whisper secrets about Paleolithic life. Iron oxide pigments were mixed with animal fat and applied with fingers, frayed twigs, or hollow bones acting as primitive airbrushes. Analysis reveals that artists sometimes used the cave's natural contours like a prehistoric 3D canvas – a swelling in the rock becoming a bison's hump, a stalactite forming a leg. Most intriguing are the multiple layers of paintings, showing generations returning to the same sacred space, each adding to the collective vision. Some figures were scored into the stone first, their outlines visible beneath the pigment like ghostly precursors.

Recent hyperspectral imaging has uncovered startling details invisible to the naked eye – vanished herds of animals whose faint traces linger beneath the famous bison, entire compositions erased by time or deliberately painted over. This palimpsest effect suggests the cave was less a gallery than a living document, constantly revised like some primordial storyboard. The famous polychrome bison ceiling may represent the final masterpiece in a sequence spanning centuries, each layer containing coded information about climate shifts, migratory patterns, or spiritual beliefs we can only guess at.

Contemporary researchers using flickering torchlight – the sole illumination available to the original artists – have discovered something extraordinary. The bison appear to move and breathe in the unstable light, their shadows creating an early animation effect. This wasn't just art for art's sake; it was likely part of an immersive ritual experience where the boundary between painter, painting, and participant dissolved. The cave's acoustics amplify certain frequencies, suggesting chanting or drumming may have accompanied these visual spectacles, creating a multisensory environment predating modern virtual reality by thousands of generations.

Conservation efforts now protect these fragile images from human breath and humidity, but the paintings continue to evolve in unexpected ways. Microbial analysis has revealed an entire ecosystem of extremophile bacteria living within the pigment layers, microscopic descendants of organisms present during the painting's creation. These microbes metabolize the ancient organic compounds in the paints, meaning the artwork quite literally lives and breathes. In this light, the Altamira bison become more than artifacts – they're symbiotic collaborations between human culture and biological processes, still dynamic after all these millennia.

The bison's cultural afterlife proves equally fascinating. Picasso reportedly emerged from Altamira saying "After Altamira, all is decadence," while modern artists from Jackson Pollock to Anselm Kiefer have drawn inspiration from these primal forms. Neuroscientists note how the paintings activate the same brain regions stimulated by contemporary art, suggesting hardwired aesthetic responses. Meanwhile, indigenous groups worldwide recognize in these images familiar traditions of sacred cave art, creating unexpected dialogues across time and continents.

Perhaps most remarkably, the Altamira artists left no evidence of themselves – no handprints (common in other caves), no obvious signatures. Their entire focus remained on capturing the essence of the animals they depended upon for survival. In doing so, they achieved something alchemical: transforming mineral pigments and cave walls into eternal life. The bison will never decay, never die, never cease their charge across the limestone sky. They represent humanity's first successful defiance of mortality, our original declaration that some things deserve to last forever.

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025