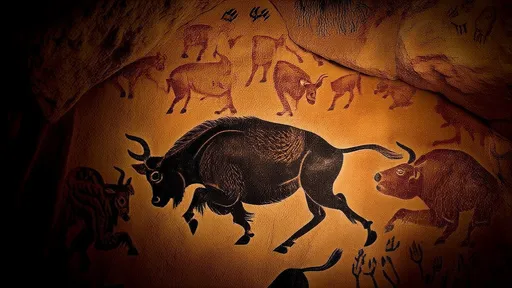

The intricate animal motifs adorning Shang and Zhou dynasty bronze vessels whisper secrets of a lost spiritual world. These zoomorphic designs – far more than decorative elements – served as sacred intermediaries between humans and the divine during ceremonial rites that shaped early Chinese civilization.

Archaeologists have identified over thirty distinct creature types cast into ritual bronzes, ranging from the ubiquitous taotie (a composite mythological beast) to remarkably naturalistic depictions of owls, buffalo, and cicadas. What makes these motifs extraordinary is their deliberate distortion – eyes bulge in impossible proportions, bodies twist into impossible angles, and multiple creatures often merge into a single terrifying visage. This wasn't poor craftsmanship, but rather a sophisticated visual language. The distortions amplified the creatures' spiritual potency, transforming them into suitable vessels for channeling ancestral powers during sacrifices.

Recent scholarship reveals fascinating regional variations in these animal codes. Early Shang designs from Anyang favored segmented creatures with exaggerated jaws, possibly reflecting shamanic traditions of spirit possession. By contrast, Zhou-era bronzes from the Wei River valley showcase elegant bird motifs with flowing crests – some scholars interpret these as celestial messengers linked to the Zhou's claimed "Mandate of Heaven." The famous Houmuwu ding, weighing 832 kilograms, presents a particularly intriguing case: its handles form biting tigers, while the main surface shows a bovine creature dissolving into geometric patterns, perhaps symbolizing the transformation of sacrificial offerings.

Beyond their terrifying appearance, these creatures fulfilled specific ritual functions. Tigers represented military power – vessels with tiger motifs often accompanied high-ranking warriors to their graves. Serpentine dragons symbolized water deities and appeared on wine vessels used for rain petitions. Most enigmatic are the back-to-back animal pairs found on late Shang zun wine containers, which some researchers believe depict spirit doubles facilitating communication between worlds.

The casting process itself held ritual significance. Analysis of bronze fragments shows that artisans sometimes intentionally buried flawed vessels – not because they were unusable, but because the act of creation mattered more than the final product. A broken wine vessel from Zhengzhou bears incomplete animal faces, suggesting the design became spiritually "activated" only through proper ceremonial use.

Modern imaging technology has uncovered astonishing details invisible to the naked eye. CT scans of a supposedly plain jue vessel from the Shanghai Museum revealed microscopic owl engravings hidden beneath patina. Even more remarkably, spectral analysis of a damaged you container in Taipei detected traces of bovine blood within the grooves of its tiger motif, physically confirming ancient accounts of blood sacrifice rituals.

These animal codes gradually faded after the Western Zhou period as human-centered philosophies emerged. Yet their legacy persists – the same creatures that once adorned sacrificial bronzes now stare back from modern temple roofs and festival masks, their primal power diminished but never fully extinguished. As archaeologist Li Xueqin noted, "To understand China's spiritual roots, one must first decipher the silent roars of these bronze beasts."

The study of these motifs continues to revolutionize our understanding of early Chinese thought. Unlike Western traditions that often separate the divine from the natural world, Shang and Zhou artisans created a fluid cosmology where animals served as bridges between realms. Their bronze menagerie reflects a worldview where every creature – real or imagined – held potential sacred significance, waiting to be unlocked through proper ritual.

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025