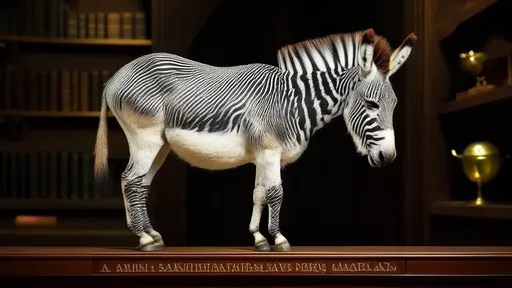

The quagga, a peculiar half-striped zebra-like creature that once roamed the plains of South Africa, has long captured the imagination of scientists and historians alike. Its unique appearance—striped only on the front half of its body—made it one of nature’s most curious anomalies. Today, preserved quagga specimens in museums serve as silent witnesses to a species that vanished over a century ago, yet their legacy continues to spark debates about extinction, genetic resurrection, and the blurred lines between myth and reality.

Discovered by European settlers in the 17th century, the quagga was initially dismissed as a strange hybrid or a freak of nature. Its name, derived from the Khoikhoi language, imitated the distinctive call it made—a sharp "kwa-ha-ha." Unlike the bold black-and-white stripes of its zebra cousins, the quagga’s stripes faded into a plain brown hindquarters, giving it an almost unfinished appearance. This striking visual contrast led to wild speculation. Some believed it was a cross between a zebra and a horse, while others thought it represented an evolutionary transition. The truth, as science would later reveal, was far more fascinating.

By the late 19th century, the quagga was hunted to extinction, prized for its meat and hide, and displaced by expanding farmland. The last known individual died in captivity at the Amsterdam Zoo in 1883, leaving behind only a handful of skins and skeletons. For decades, the quagga was relegated to the footnotes of natural history—until DNA technology revived interest in its story. In the 1980s, genetic analysis of preserved quagga specimens revealed a startling fact: the quagga wasn’t a separate species at all, but a southern subspecies of the plains zebra. This discovery upended traditional classifications and raised provocative questions about how we define species.

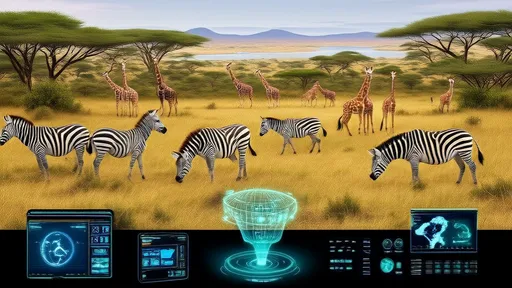

The quagga’s genetic legacy didn’t end there. In a controversial project launched in 1987, scientists attempted to "bring back" the quagga through selective breeding of plains zebras with reduced striping. Known as the Quagga Project, this effort has produced zebras that visually resemble the extinct animal, though critics argue it’s more of a symbolic resurrection than a true revival. Supporters, however, see it as a chance to correct a human-caused extinction, if only in appearance. The project’s zebras, now roaming private reserves in South Africa, serve as living reminders of how easily species can vanish—and how far we might go to undo the damage.

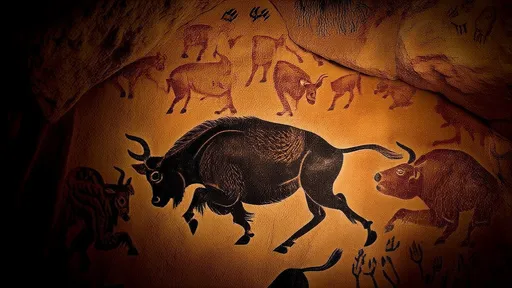

Beyond science, the quagga has seeped into culture and folklore. Its enigmatic appearance has inspired art, literature, and even cryptozoological theories. Some have wondered if isolated quaggas might still exist in remote valleys, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Others see the quagga as a cautionary tale about humanity’s reckless exploitation of nature. Museums displaying quagga specimens often frame them as relics of a lost world, prompting visitors to reflect on biodiversity and conservation.

Today, the quagga remains a powerful symbol—not just of extinction, but of the complexities of evolution and classification. Its story challenges our assumptions about what makes a species distinct and how much of nature’s diversity we’ve already lost without fully understanding it. The preserved hides and bones in museum collections are more than just artifacts; they’re fragments of a puzzle that science is still piecing together. Whether through DNA studies or breeding experiments, the quagga continues to gallop through our collective curiosity, a half-striped ghost bridging myth and reality.

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025